In Syria’s largest Palestinian refugee camp, the final school lessons concluded on October 18 2012, as evidenced by the date still visible on the chalkboard more than ten years later.

Sentences such as “I am playing football,” “She is eating an apple,” and “The boys are flying a kite” are examples of English language structure.

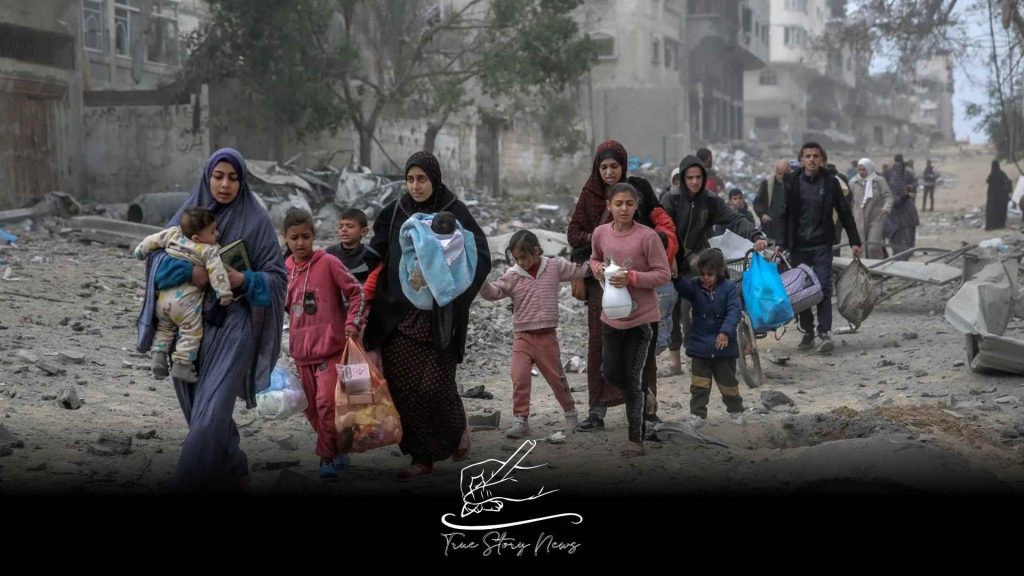

In the Damascus suburb of Yarmuk, children are seen playing amidst the remnants of destruction caused by years of civil conflict in Syria.

As children dart through clouds of concrete dust, a recently liberated torture victim, freed from prison this month following the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, makes his way through the debris.

“Since my release from prison, I have been sleeping a maximum of one or two hours,” said 30-year-old Mahmud Khaled Ajaj in an interview with AFP.

Established in 1957, Yarmuk spans 2.1 square kilometres (519 acres) and serves as a “refugee camp” for Palestinians who were displaced following the creation of the modern Israeli state.

The city lies in ruins

Over the decades, this camp, like others throughout the Middle East, has evolved into a densely populated urban community characterized by multi-storey concrete housing blocks and various businesses.

The United Nations agency for Palestinian refugees, known as UNRWA, reported that at the onset of Syria’s conflict in 2011, the country was home to 160,000 registered refugees.

By September of this year, the area had been ravaged by rebellion, air strikes, and a siege imposed by government forces, leaving a mere 8,160 individuals struggling to survive amidst the devastation.

As the regime of Assad crumbles, there is hope for the reopening of damaged schools and mosques, prompting a potential return for many. However, individuals such as Ajaj carry harrowing stories of persecution endured under Assad’s rule.

A former fighter of the Free Syrian Army endured seven years in government detention, primarily at the infamous Saydnaya prison, and was ultimately freed following the conclusion of Assad’s regime on December 8.

Ajaj’s complexion remains notably lighter than his neighbours, who have developed a sun-kissed tan from spending time outside their damaged residences. He moves with difficulty, aided by a back brace, a consequence of enduring years of physical abuse.

A prison doctor once administered an injection to his spine, resulting in partial paralysis, a move he suspects was intentional. However, it is the relentless hunger experienced in his overcrowded cell that continues to haunt him the most.

Neighbours and relatives are aware of my limited food supply, prompting them to bring me meals and fruit. Sleep eludes me when food is not within reach. “The bread, particularly the bread,” he remarked.

“Yesterday, we had bread leftovers,” he remarked, savouring the fresh air after being confined in a windowless group cell while dismissing calls from his family urging him to visit a worried aunt.

My parents typically reserve them for the birds to provide nourishment. I instructed them to allocate a portion to the birds while reserving the remainder for my use. “Regardless of their condition, whether dry or old, I desire them for myself.”

While speaking to AFP, Ajaj caught the attention of two Palestinian women who stopped to inquire about any updates regarding their missing relatives following the flight of Syria’s ousted leader to Russia.

The International Committee of the Red Cross has reported over 35,000 instances of disappearances occurring during Assad’s regime.

Ajaj’s ordeal highlights the severe challenges faced by the Yarmuk community, which has been caught in the crossfire of Assad’s war for survival. The situation has forced Palestinians into combat roles on opposing sides, further complicating an already dire humanitarian crisis.

Bullets embedded

The graveyard bears the scars of air strikes, marked by deep craters. Amid the devastation, families face significant challenges in locating the tombs of their deceased loved ones. Empty basketball courts bear the visible scars of mortar strikes.

Bulldozers are seen manoeuvring through piles of rubble while individuals experiencing homelessness search for reusable materials among the debris. While some individuals manage to secure employment, others continue to grapple with the effects of trauma.

Haitham Hassan al-Nada, a vibrant 28-year-old with wild eyes, extended an invitation to an AFP reporter to feel the lumps he claims are bullets still embedded in his skull and hands.

After being shot and left for dead by Assad’s forces as a deserter from the government side, he receives support from his father, a local trader, who helps him, his wife, and their two children.

Nada stated to AFP that he left the military service because, as a Palestinian, he believed it was unjust for him to serve in the Syrian forces. He reported that he was apprehended and shot multiple times.

After the incident, my mother received a call, prompting her to head towards the airport road toward Najha. He recounted, “They informed her, ‘This is the dog’s body, the deserter.’

“My body was not washed, and as she leaned in to kiss me goodbye before the burial, something extraordinary happened. In a moment that felt divine, I took a deep breath.”

Upon his release from the hospital, Nada returned to Yarmuk, where he encountered a destroyed landscape.